In 2021, the Task Force on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets suggested that a 10x to 100x increase in the use of carbon offsets is needed to deploy the “climate capital” around the world to meet global climate targets. Under this scenario, between tens and hundreds of billions of dollars would be spent annually on carbon offsets.

Not surprisingly, this forecast generated considerable investor interest. But investors should recall that carbon offsets have been a controversial and volatile commodity since the first carbon offset in 1988. Realistically, there are BIG uncertainties about whether the carbon market can live up to “offset-optimist” expectations.

Given the stakes when it comes both to investors and climate change, and what seems like growing confusion regarding how companies, investors, and even the general public should think about carbon offsets, I’ve structured this 3-part blog series as a brief “due diligence” into the future of offset markets. The three parts are:

Part 2: The Challenges of Building a Market Around an Intangible Commodity

Part 3: Anticipating Carbon Offset Futures

Because carbon offsets have become so polarized in climate change mitigation circles, I include a somewhat detailed personal “offsets bio” below, so you as a reader will know my background in the area and can decide how much credence to give my thinking and conclusions.

Part 3: Anticipating the Future of Carbon Offsets

In Part 1 of this series I reviewed the history of carbon offsets and the “small world model” that underlies much of the thinking about carbon offsets. In Part 2, I explored the challenges of extrapolating from that small world model to what happens in the real world, particularly when dealing with an entirely intangible commodity. Here in the third and final post in this series, I suggest there is both good news and bad news with respect to carbon offsets, and explore alternative scenarios for their future.

Fair warning, Part 3 builds on the necessary wonkiness of Part 2, exploring issues rarely if ever explicitly raised in offsets conversations. And I recognize that both “offset-optimists” and “never-offsetters” will find plenty to want to disagree with.

Here are the core elements of Part 3:

· Without “adequate” integrity, there is no justification for offset markets

· Offsets markets can deliver a quality commodity, and can (in principle) scale

· An intangible commodity, however, can’t scale indefinitely.

· Several scenarios exist for where offsets go from here

The ”Need” for Carbon Offsets Can’t Justify an “Inadequate-Integrity” Market

Offset advocates often start the conversation with the assertion that we “need” offsets to accomplish a range of desired outcomes, from decarbonization to climate finance and climate justice. I remember giving a talk more than 20 years ago where the first audience comment was: “We don’t have time to worry about things like additionality. Climate change is simply too important; we need to be doing all we can, all the time.” Does that suggest we should accept a carbon market composed of only 5% legitimate offsets, a plausible outcome if the additionality criterion is abandoned? I would hope not.

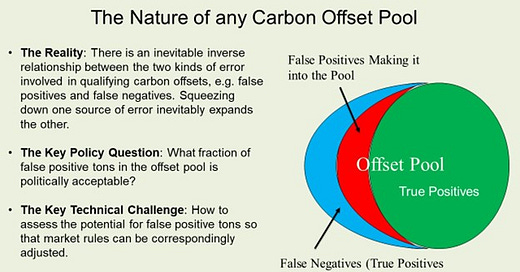

But, as discussed in Part 2 and summarized in the illustration below, a 100% legitimate offset market is not possible either. The important policy question, therefore, is what is “good enough” when it comes to market integrity? Is it a 90/10 ratio of high-confidence offsets (true positives) to low-confidence offsets (false positives) making it to market? What about 80/20, 70/30, or 60/40?

There is no technically “correct” answer to the question of “adequate” market integrity. Even so, the level of market integrity is a critical policy question in designing offset markets. Yet offset market designers don’t ask the question, much less answer it. Most market participants assume that a 100% legitimate offset market is possible. The fact that the question doesn’t get asked or answered helps explain how we’ve gotten to a situation in which multiple studies of offset markets have suggested a ratio closer to 20/80 than 80/20.

The Good News – Carbon Offset Markets Can Be Designed to Work (at Least at Some Scale)

The fact that offset markets haven’t been designed well to date doesn’t mean they can’t be. To the contrary, carbon offset markets can be designed to deliver adequate environmental integrity -- however that is defined -- as long as it’s well short of 100%. And if designed well, offset markets can scale, albeit not to the level offset-optimists would like to see. But scaling offsets requires thinking very carefully about what’s allowed into the “potential” offset pool and balancing the size of that pool with offset demand.

A Roadmap for Creating and Maintaining Market Integrity

The next several graphics roadmap the steps that would deliver a quality (e.g. adequate integrity) market. To keep the discussion and the slides as simple as possible, I’ll pretend that “additionality” is the only qualifying criterion for offsets.

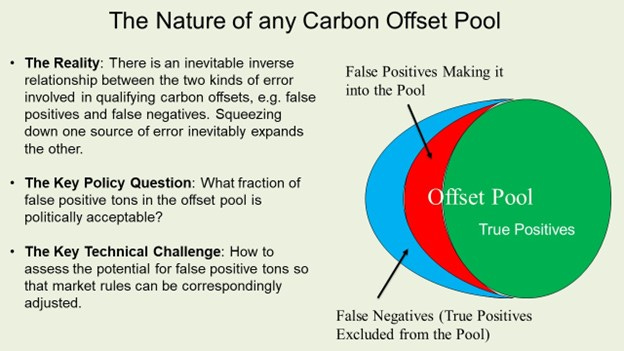

1. As already noted, the “potential” offset supply is enormous (absent consideration of things like additionality, permanence, and leakage). Not surprisingly, as shown below, most of that “potential” supply wouldn’t satisfy those important criteria.

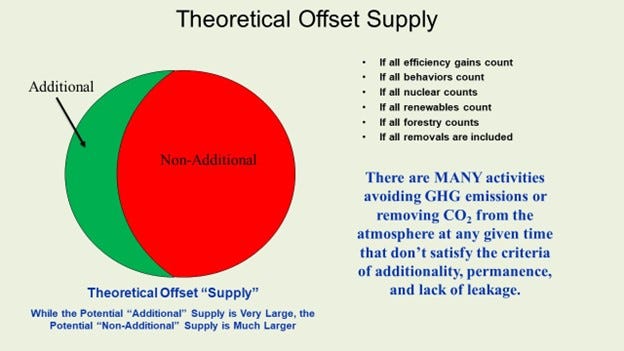

2. If the question of additionality is ignored when it comes to qualifying “potential tons” for the offset market, a non-additional market outcome is inevitable. There is no reason to bring higher risk and higher cost legitimate offsets to market if lower cost and lower risk non-additional tons can be sold as offsets, and there are plenty of non-additional tons available to meet demand.

3. What if we radically increase demand, sticking to the same unscreened “potential pool”? If demand scales up enough, legitimately additional tons will start to show up in the market, but the market will remain dominated by low-quality tons.

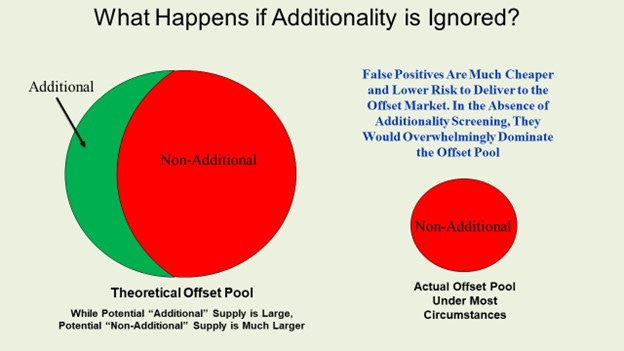

4. Conversely, just improving the quality of the “potential pool” by carefully screening for the sectors and projects allowed to participate in the market won’t be enough if there is a substantial imbalance between supply and demand. The greater the imbalance between supply and demand, the easier it will be to satisfy demand with non-additional tons from the “potential pool.”

5. Creating and maintaining a quality offset market requires balancing the size of the “potential pool” with offset demand. Successfully maintaining offset quality while scaling that market requires keeping supply and demand in balance. As demand increases, for example, additional sources of offsets can be added to the “potential pool.” As previously noted, a 100% additional offset market will never be possible -- but careful attention to what “additional sources of offsets” are allowed into the pool can maintain adequate environmental integrity.

How to Fix Offset Markets

As one carbon offset expert summarizes today’s situation: “at the project level, everyone kind of has an incentive to see how much they can get away with without raising alarm bells among buyers - but the systemic outcome is a crash.”

The good news is that there are several key steps we could take to substantially improve offset market outcomes.

Decide how the goals of offset cost-effectiveness and environmental integrity are to be balanced in evaluating and approving offsets. Only then can “appropriate” rules for implementing the additionality, permanence, and leakage criteria be developed.

Since a “perfect” offset pool is out of reach, decide “how good is good enough.”

In creating the “potential offset pool” through the approval of offset methodologies, each methodology should be required to evaluate the potential for non-additional tons to use that methodology to qualify as offsets.

Anticipate the inevitability of gaming and write offset rules accordingly.

Use third-party “quality due diligence” reviews to inform offset buyers about how much confidence they should have when purchasing offsets.

The relatively recent launch of multiple offsets ratings agencies represents progress on at least one of these steps. And the question really isn’t whether one could “fix” today’s offset markets, it’s whether market participants have any interest in doing so given the market implications -- a topic we’ll come back to below.

The Bad News – Once “Fixed,” Offsets Markets Won’t Scale to Meet Todays Overly-Ambitious Market Expectations

With careful attention to how offset markets are structured, those markets could significantly scale. The challenge comes in assuming that offsets can scale to the point of playing a major role in achieving global climate targets, as assumed by offset optimists.

The problem is two-fold. First, as more offset sources are added to the potential pool in order to meet rising demand, it inevitably gets harder to manage the number of false positives making it into the pool. Second, the intangibility of the offset commodity, as explored in Part 2, makes it harder to limit gaming, fraud, and corruption in the market as the market gets larger and encompasses more and more offset sources. We’ve seen both of these problems even with the relatively modest scaling of carbon offset markets attempted to date, which is a far cry from the massive scaling proposed by offset optimists.

Alternative Offset Scenarios

So where does that leave us when thinking about the future of carbon offsets? I’ll briefly explore a few of the potential scenarios.

Scenario 1: We Fix Offset Markets

I’ve noted that the question really isn’t whether one could “fix” today’s offset markets; we could. But do we really want to? Most of today’s offset market participants would object for one reason or another to the likely implications of a quality offset market, including:

Greater centralization, since the idea that anyone can set up their own offset standards organization and market undermines efforts to deliver a quality commodity.

Greater business risk, as the ability of market participants to game offset rules declines.

Fewer categories of qualifying projects, e.g. due to stricter application of qualifying criteria, permanence and leakage in particular.

Fewer qualifying projects in each category, e.g. due to stricter application of qualifying criteria, additionality in particular.

Smaller size, with less growth potential.

Substantially higher market prices.

Whether because of greater business risk, limited growth potential, or substantially higher market prices, there is something for everyone to hate about the design parameters of a quality offset market. And because offset market stakeholders dominate efforts to “fix” offset markets, we are far more likely to continue to see efforts that nibble around the edges of the problems as opposed to solving them.

Even the ICVCM’s proposed Assessment Framework does little to address the challenges we explored in Part 2 of this series. The ICVCM makes no mention of the problems created by scaling offsets beyond their “small world model,” for example, nor does it discuss the reality that we can’t be certain of an intangible commodity’s quality (just more or less confident). Finally, the ICVCM doesn’t address the need to explicitly balance the objectives of cost-effectiveness and environmental integrity. The ICVCM is dominated by current market participants and stakeholders and is trying to improve the existing carbon offset “mousetrap.” It’s not trying to rethink the system in order to deliver a consistently quality offset commodity.

For these reasons, Scenario 1 is pretty unlikely.

Scenario 2: Full Speed Ahead on Offsets

Many offset market participants and investors are banking on a “full speed ahead” future for voluntary offsets and offset markets. This scenario includes many of the elements described in Scenario 1 when it comes to nibbling around the edges of the problem. Nevertheless, this scenario requires arguably heroic assumptions about the ability of market participants to continue to distract attention from the structural problems with carbon offsets. Admittedly, as Margaret Heffernan notes, our proven potential for “willful blindness” is huge.

Given the commonly cited “need” for carbon offsets to tackle climate change, this scenario is quite likely in the short- to medium-terms. That said, willful blindness cannot succeed forever as a market strategy. If offsets scale rapidly under Offsets Round 2, all other things being equal, the result is likely to be the same kind of crash that ended Offsets Round 1.

Scenario 3: From Projects to Programs

Some offset market observers suggest that the problem with today’s offset markets is the focus on a myriad of individual projects, each delivering a relatively small quantity of offsets. They suggest that a “programmatic approach” based, for example, on public policies intended to generate qualifying reductions and removals could be much simpler to implement and ultimately more effective.

But there is nothing about a programmatic approach that inherently solves the “intangibility” problems discussed in Part 2 of this blog series. Indeed, the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism experimented with programmatic offset methodologies; the problems encountered didn’t differ much from the project-based approach.

Scenario 4: From Carbon Offsets to Carbon Contribution Claims

Recently, there has been discussion of moving away from focusing on “carbon offsets” to the alternative idea of “carbon contributions.” Carbon contributions are different because the funder in a contribution claims model doesn’t claim ownership of any emissions reductions or carbon removals resulting from the “contribution.” As a result, those emissions reductions or removals can’t be applied against the funder’s carbon footprint-related claims, e.g. climate neutrality or net zero.

“Carbon contributions” could fund many of the same types of initiatives being funded by carbon offsets, but could also apply to activities that wouldn’t be able to qualify as offsets, e.g. climate education and policy advocacy. In effect, carbon contribution claims would encourage companies to spend money on what will most advance global climate objectives, as opposed to focusing on their individual carbon footprints.

To the extent carbon contribution claims aren’t counted against your emissions footprint, do things like additionality, leakage, and permanence still matter? They certainly matter less since you are not implicitly justifying an emission somewhere else with a contribution claim, as you are with a carbon offset. That said, if you’re going to give contribution claim money to someone to mitigate climate change, you would still want to fund something that wouldn’t have otherwise happened – i.e., the importance of additionality still exists. Moreover, you would still want to promote activities that might have a permanent impact and which don't leak. So, in a very real sense, additionality, permanence, and leakage are just as conceptually important, but arguably pose much less of a greenwashing problem than they do for today’s carbon offsets.

A growing number of carbon offset market participants are promoting the substitution of contribution claims for carbon offsets. Whether individuals, companies, or countries will have any interest in funding “contribution claims” that can’t be applied against their footprints or net zero targets, however, remains an untested proposition.

Conclusion

In this blog series I’ve laid out in some detail the challenges of building a quality commodity market around an intangible commodity like carbon offsets. Offset optimists assert that offsets can be scaled by 10x to 100x to help meet global climate targets, with no discussion of the challenges I’ve discussed. Nor is there any such discussion in the more recent work of the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market. Instead, offset advocates state the “need” for carbon offsets, assume that there are simple technical fixes that can be implemented for carbon markets, and assume that offsets can be massively scaled. These are completely unproven assumptions and should be treated skeptically unless demonstrated otherwise.

The future of offset markets, and the ability of investors to profit from them, can only be characterized as radically uncertain. Offset markets could evolve in many different ways, with the “explosive growth” scenario being both the most likely and the most risky. These markets have collapsed before, and if we simply continue with offsets business as usual, including ineffective efforts to “fix” offset markets, they probably will again. If you’re banking on carbon offsets, tread carefully.

Offsets Bio: Dr. Mark C. Trexler was hired by the World Resources Institute (WRI) in 1988 to work on the first carbon offset. At WRI, he also carried out some of the first studies of “nature-based climate solutions,” work he continued as a Lead Author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Second Assessment Report, and as the Editor for the carbon offsets chapter of the IPCC’s Special Report on Land Use and Land Use Change in 1996. Mark left WRI in 1991 to found the first U.S. climate advisory firm focused on business risk assessment and management, later acquired by EcoSecurities, an international carbon trading firm based in Oxford, England. In these roles he worked extensively on carbon offset projects around the world, and was responsible for developing carbon offset methodologies including coal-mine methane recovery and ocean fertilization.

Mark is widely published on the topic of carbon offset markets and the importance of “additionality” in determining the integrity of offset markets. In 2008, while at EcoSecurities, Mark’s team developed the first sophisticated carbon offsets rating system, based on a 0-1000 score representing how confident buyers should be in the quality of specific offsets. The ratings system was shelved due to fears it would undermine EcoSecurities’ business model and disrupt voluntary carbon markets. The most innovative element of the scoring system, an “inverse weighting” algorithm that makes it impossible for an offset to be rated highly without performing well against all three core criteria of additionality, permanence, and the lack of leakage, was eventually incorporated into the Carbon Credit Quality Initiative.

Today, Mark’s focus is primarily climate risk under-estimation and climate risk knowledge management. The Climatographers’ Climate Web knowledge solution is the closest thing to a collective intelligence for business as well as societal climate risk assessment and management. He continues to track carbon offsets and markets, but other than offering “due diligence” advisory services to projects and companies trying to understand and anticipate carbon markets, he has no financial interests in those markets. Mark is reachable at mark@climatographer.com.